Chapter 10 County-Level Data

SRS data is only available at the agency-level.66 This has caused a lot of problems for researchers because many variables from other data sets (e.g. CDC data, economic data) is primarily available at the county-level. Their solution to this problem is to aggregate the data to the county-level by summing all the agencies in a particular county.67

More specifically, nearly all researchers who use this county-level data use the National Archive for Criminal Justice Data (NACJD)’s data sets which have done the aggregation themselves68. These are not official FBI data sets but “UCR staff were consulted in developing the new adjustment procedures”.69 The “new” procedures is because NACJD changed their missing data imputation procedure starting with 1994 SRS data, and for this chapter I will only focus on this “new” procedure.

It makes sense to aggregate SRS data to the county-level. That level is often times more useful to analyze than the agency-level. But there are two problems with county-level SRS data: 1) agencies in multiple counties, 2) and agencies with missing data.70

The first issue is in distributing crimes across counties when an agency is in multiple counties. If, for example, New York City had 100 murders in a given year, how do you create county-level data from this? SRS data only tells you how many crimes happened in a particular agency, not where in the jurisdiction it happened. So we have no idea how many of these 100 murders happened in Kings County, how many happened in Bronx County, and so on.

SRS data does, however, tell you how many counties the agency is in and the population of each. They only do this for up to three counties so in cases like New York City you do not actually have every county the agency is part of.71 NACJD’s method is to distribute crimes according to the population of the agency in each county. In the New York City example, Kings County is home to about 31% of the people in NYC while Bronx County is home to about 17%. So Kings County would get 31 murders while Bronx County gets 17 murders. The problem with this is the crime is not evenly distributed by population. Indeed, crime is generally extremely concentrated in a small number of areas in a city. Even if 100% of the murders in NYC actually happened in Bronx County, only 17% would get assigned there. So for agencies in multiple counties could have their crimes distributed among their different counties incorrectly. This is not that big of a deal, however, as most agencies are only in a single county. It is likely incorrect given how crime is concentrated, but affects relatively little in our data so is not worth much worry.

The second problem is the one we need to be concerned about. This issue is that not all agencies report data, and even those that do may report only partially (e.g. report fewer than 12 months of the year). So by necessity the missing data has to be filled in somehow. All methods of estimating missing data are wrong, some are useful. How useful are the methods used for SRS data? I will argue that they are not useful enough to be used in most crime research. This is by no means the first argument against using that data. Most famously is Maltz and Targonski’s (2002) paper in the Journal of Quantitative Criminology about the issues with this data. They concluded that “Until improved methods of imputing county-level crime data are developed, tested, and implemented, they should not be used, especially in policy studies” which is a conclusion I also hold.

County-level data aggregates both crimes from the Offenses Known and Clearances by Arrests data set and arrests from the Arrests by Age, Sex, and Race data set, which has lower reporting (and thus more missingness) than the crime data. For simplicity, in this chapter we will use the crime data as an example. We will do so in a number of different ways to try to really understand how much data is missing and how it changed over time. Estimation is largely the same for arrests and county-level arrests is far less commonly used

Since these methods are for dealing with missing data, if there is no missing data then it does not matter how good or bad the estimation process is. Counties where all agencies report full data are perfectly fine to use without concerning yourself with anything from this chapter. In this chapter we will also look at where counties have missing data and how that changed over time.

10.1 Current usage

Even with the well-known flaws of this data, it remains a popular data set. A search on Google Scholar for “county-level UCR” returns 5,580 results as of this writing in summer 2024. About half of these results are from 2015 or later. In addition to use by researchers, the county-level UCR data is used by organizations such as the FBI in their annual Crimes in the United States report (which is essentially the report that informs the media and the public about crime, even though it is actually only a subset of their published UCR data) and Social Explorer, a website that makes it extremely convenient to examine US Census data.

10.2 How much data is missing

Since estimating missing data only matters when the data is missing, let us look at how many agencies report less than a full year of data.

For each of the below graphs and tables we use the Offenses Known and Clearances by Arrest data for 1960-2023 and exclude any agency that are “special jurisdictions”. Special jurisdiction agencies are, as it seems, special agencies that tend to have an extremely specific jurisdiction and goals. These include agencies such as port authorities, alcohol beverage control, university police, and airport police. These agencies tend to cover a tiny geographic area and have both very low crime and very low reporting rates.72 So to prevent missingness being overcounted due to these weird agencies I am excluding them from the below examples. I am also excluding federal agencies as these operate much the same as special jurisdiction agencies. Since some estimation is based on state-level data and I present maps that exclude territories, I am also going to subset the data to only agencies in a state or in Washington DC.

We will first look at how many months are reported in the 2017. Table 10.1 shows the number of months reported using two ways to measure how many months an agency has reported data, the “last month reported” and the “number of months missing” measure that we considered in Section 3.2. The data changed how some of the variables were used starting in 2018, making post-2017 data unreliable for the “number of months missing variable.

The table shows what percent of agencies that reported data had data for each possible number of months: 0 through 12 months. Column 2 shows the percent for the “last month reported” method while column 3 shows the percent for my “number of months missing” method. And the final column shows the percent change73 from moving from the 1st to 2nd measure.

Ultimately the measures are quite similar though systematically overcount reporting using the 1st method. Both show that about 27% of agencies reported zero months. The 1st method has about 69% of agencies reporting 12 months while the 2nd method has 66%, a difference of about 5% which is potentially a sizable difference depending on exactly which agencies are missing. The remaining nearly 4% of agencies all have far more people in the 2nd method than in the first, which is because in the 1st method those agencies are recorded as having 12 months since they reported in December but not actually all 12 months of the year. There are huge percent increases in moving from the 1st to 2nd method for 1-11 months reported though this is due to having very few agencies report this many months. Most months have only about 50 agencies in the 1st method and about 70 in the 2nd, so the actual difference is not that large.

| Months Reported | Last Month Definition | Months Not Missing Definition | Percent Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4,360 (22.55%) | 4,364 (22.57%) | +0.09 |

| 1 | 29 (0.15%) | 79 (0.41%) | +172.41 |

| 2 | 34 (0.18%) | 69 (0.36%) | +102.94 |

| 3 | 42 (0.22%) | 65 (0.34%) | +54.76 |

| 4 | 29 (0.15%) | 43 (0.22%) | +48.28 |

| 5 | 28 (0.14%) | 66 (0.34%) | +135.71 |

| 6 | 39 (0.2%) | 64 (0.33%) | +64.10 |

| 7 | 30 (0.16%) | 54 (0.28%) | +80.00 |

| 8 | 45 (0.23%) | 68 (0.35%) | +51.11 |

| 9 | 47 (0.24%) | 88 (0.46%) | +87.23 |

| 10 | 70 (0.36%) | 115 (0.59%) | +64.29 |

| 11 | 129 (0.67%) | 241 (1.25%) | +86.82 |

| 12 | 14,451 (74.75%) | 14,017 (72.5%) | -3.00 |

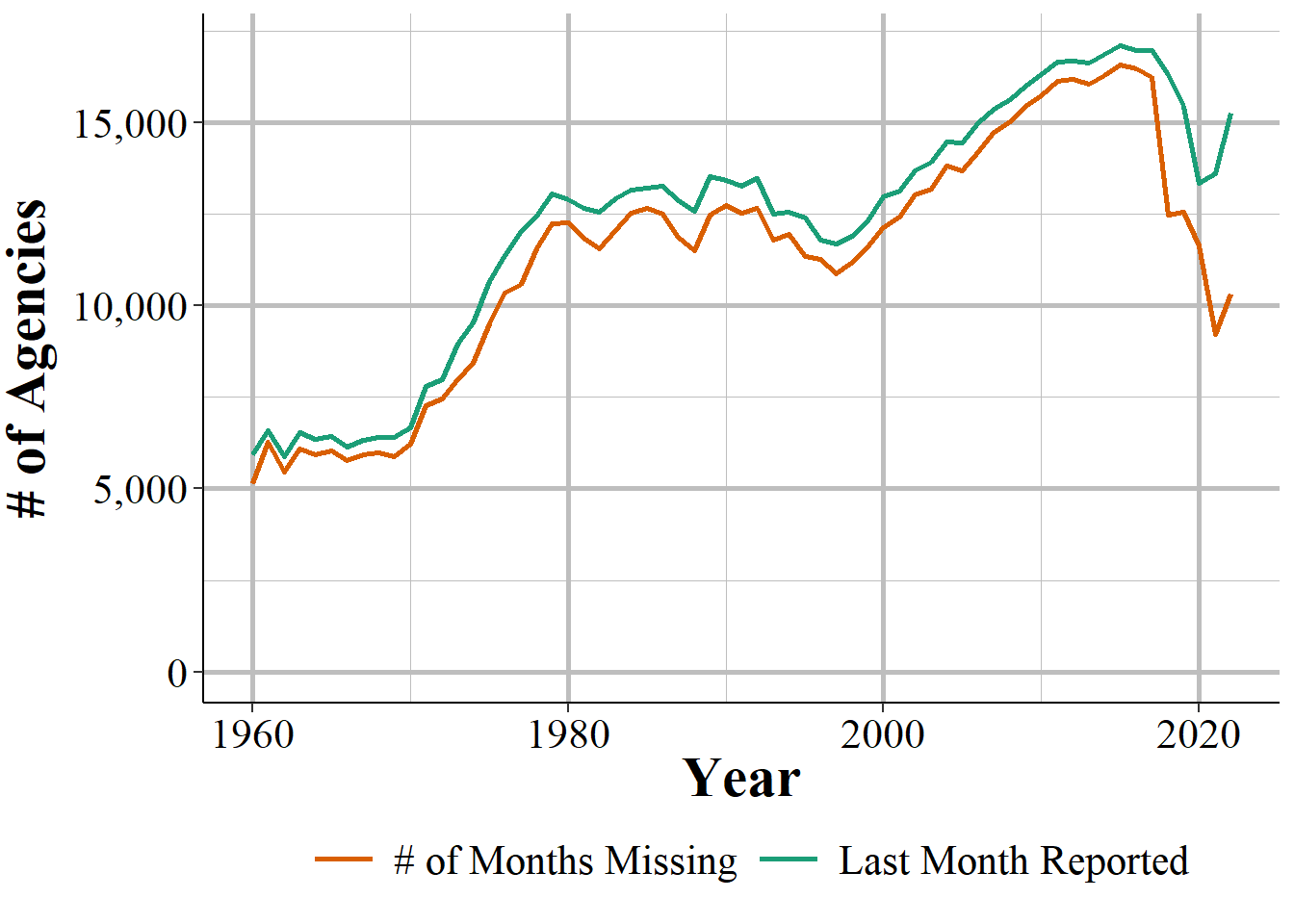

We can look at how these trends change over time in Figure 10.1 that shows the annual number of agencies that reported at least one month of data in that year. Both measures have the exact same trend with the last month reported measure always being a bit higher than the number of months missing method, at least until the data change in 2018 that renders my method unreliable.

Figure 10.1: The annual number of agencies that reported data in that year.

For the remainder of this chapter we will treat the last month reported variable as our measure of how many months an agency reports data. I believe that pre-2018 this is not as good a measure at the number of months missing, but it has the benefit of consistency post-2017. So keep in mind that the true number of agencies reporting fewer than 12 months of data is a bit larger than what it seems when using this measure.

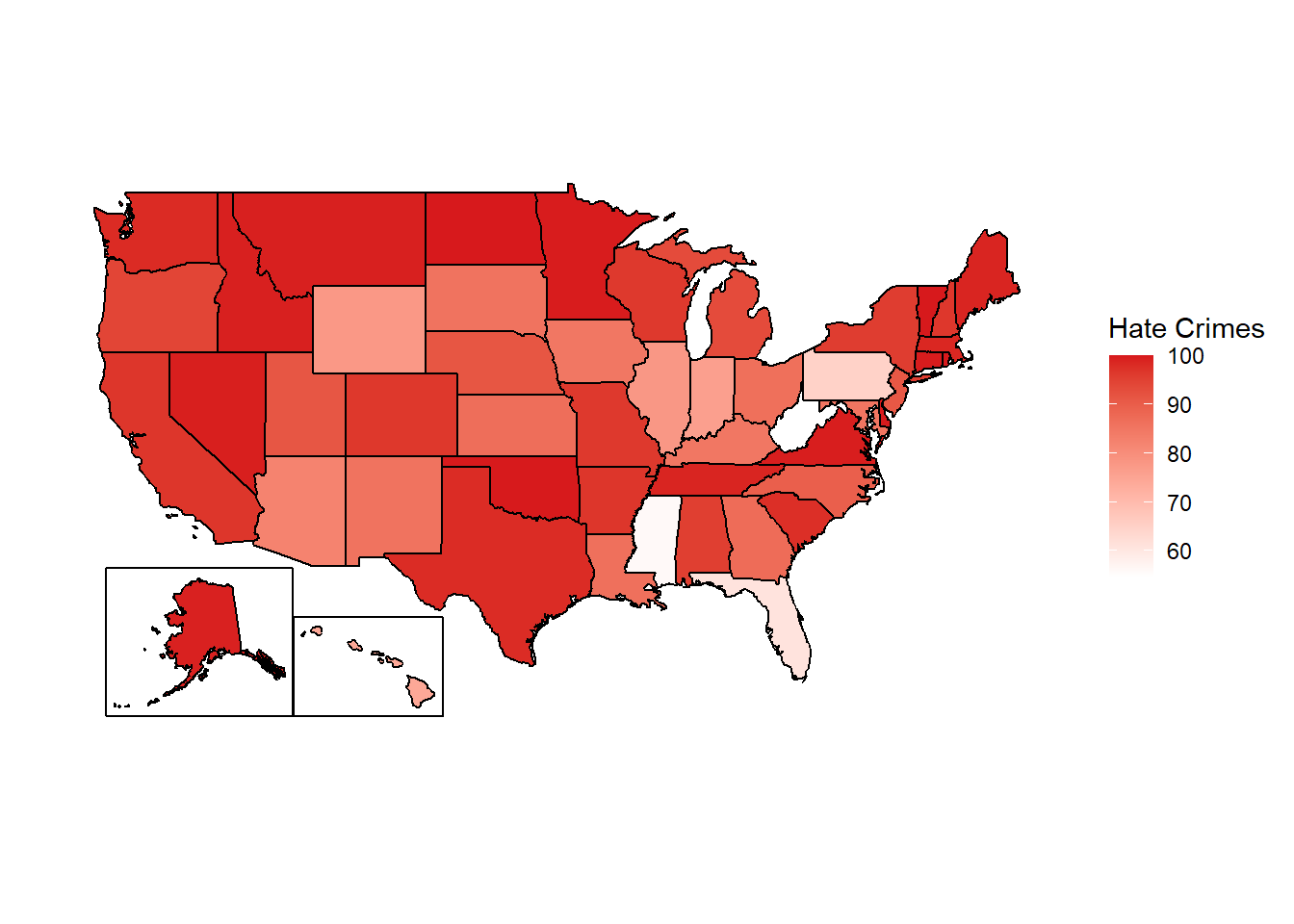

Figure 10.2: The share of the population in each state covered by an agency reporting 12 months of data based on their last month reported being December, 2023.

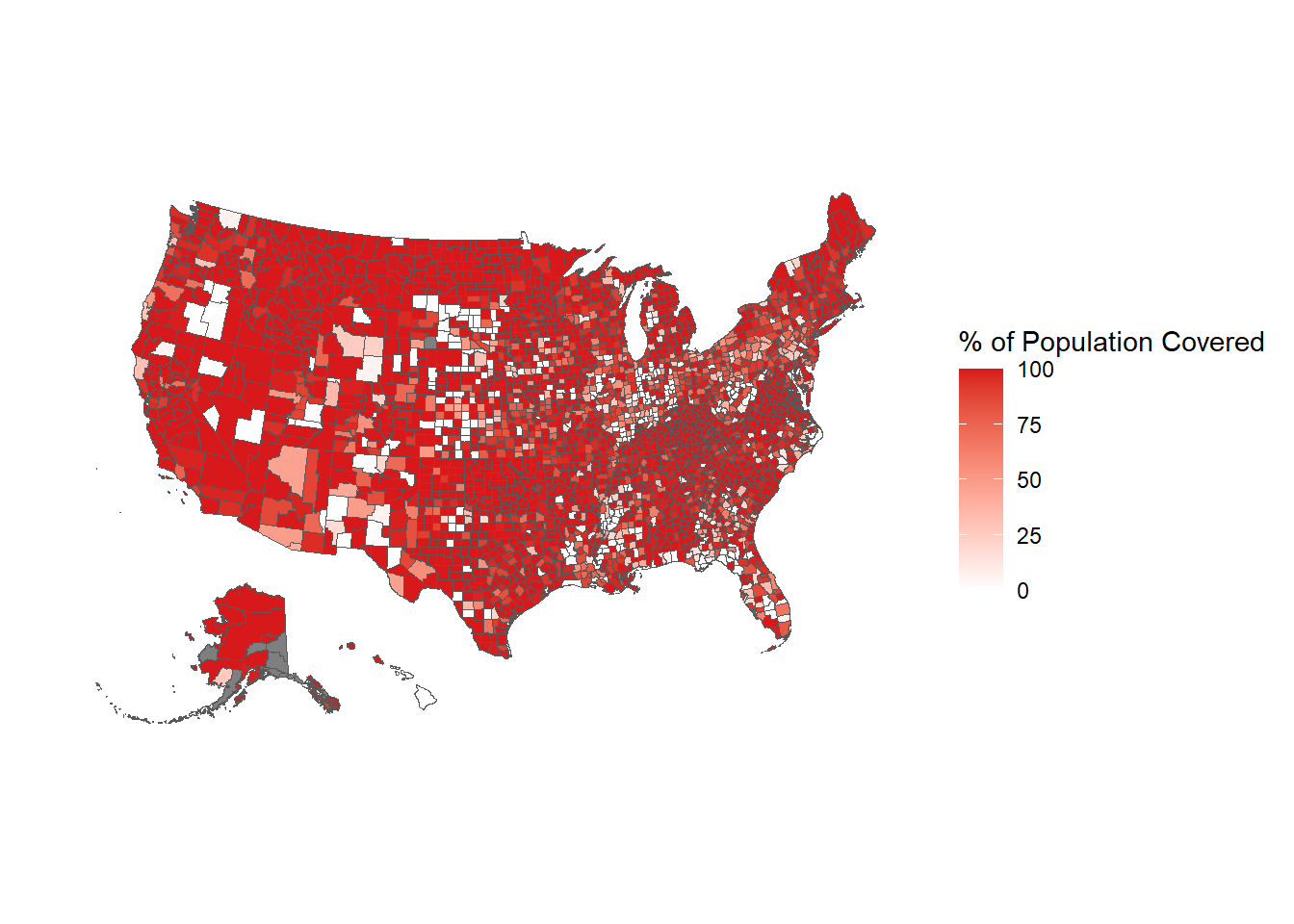

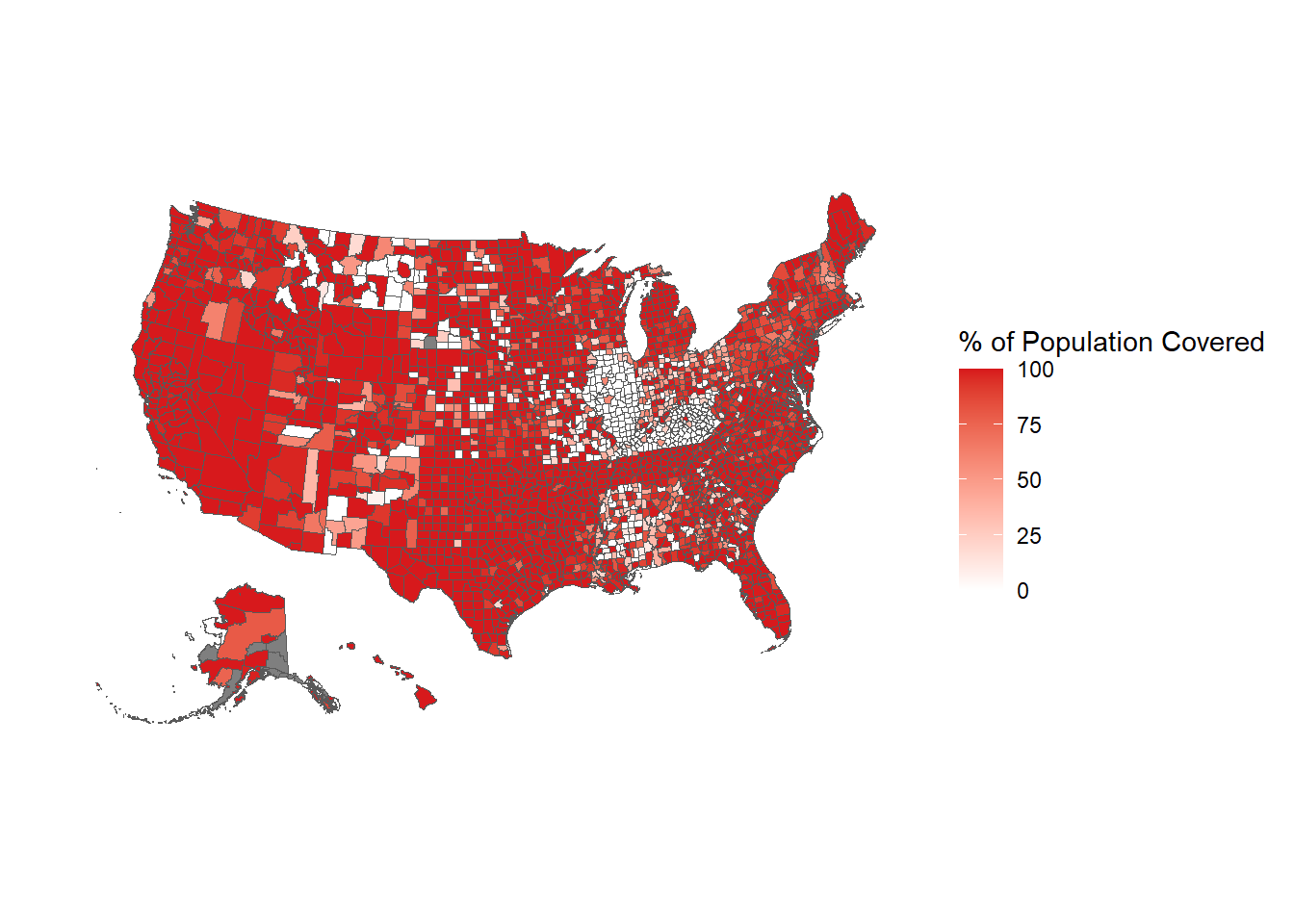

Figure 10.3: The share of the population in each county covered by an agency reporting 12 months of data based on their last month reported being December, 2023.

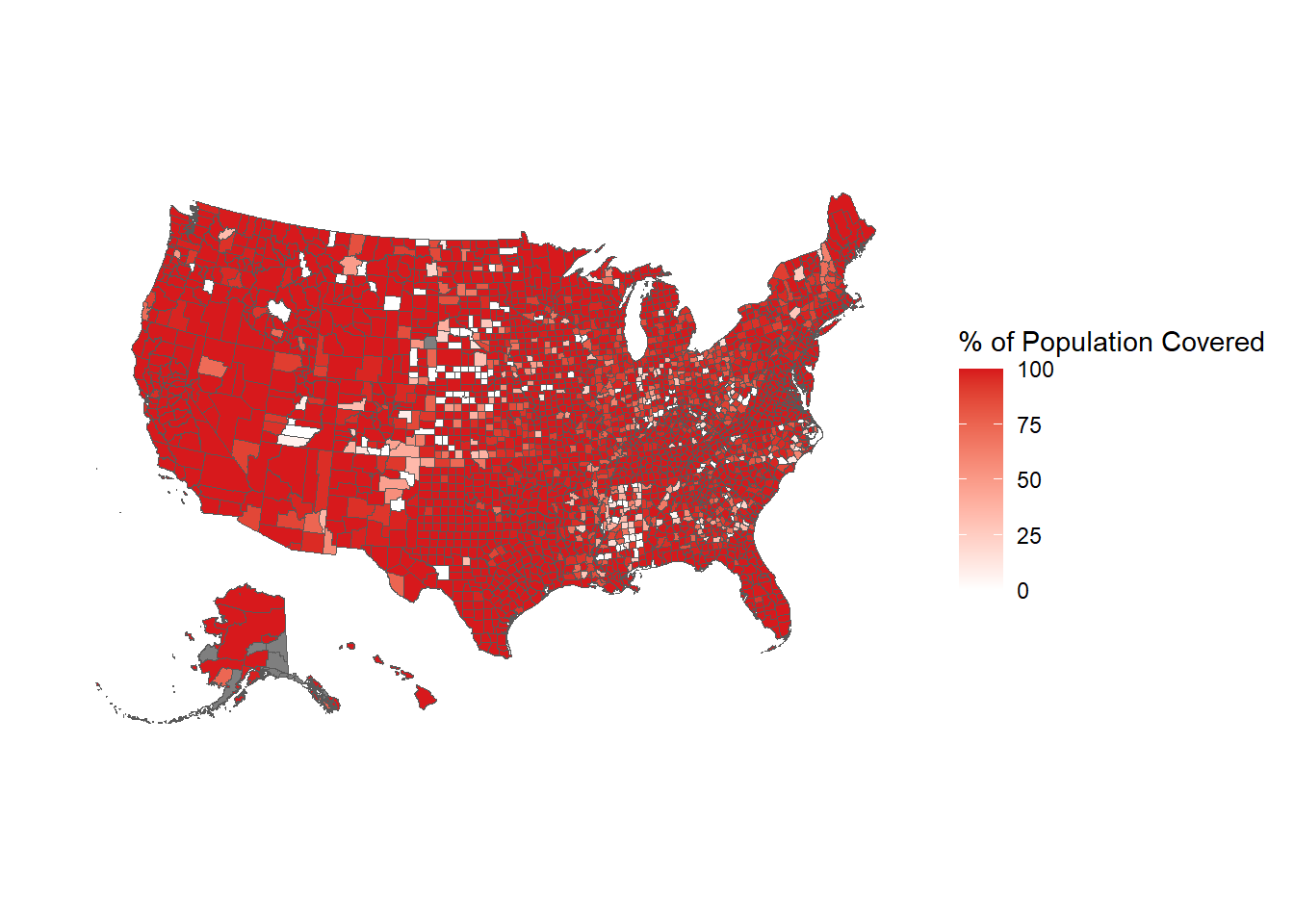

Figure 10.4: The share of the population in each county covered by an agency reporting 12 months of data based on their last month reported being December, 2010.

Figure 10.5: The share of the population in each county covered by an agency reporting 12 months of data based on their last month reported being December, 2000.

10.3 Current imputation practices

There are three paths that the county-level UCR data takes when dealing with the agency-level data before aggregating it to the county-level. The path each agency is on is dependent on how many months of data they report. Figure 10.6 shows each of these three paths. We will look in detail at these paths in the below sections, but for now we will briefly summarize each path.

First, if an agency reports only two or fewer months, the entire agency’s data (that is, any month that they do report) is deleted and their annual data is replaced with the average of agencies that are: 1) in the same state, 2) in the same population group (i.e. very roughly the same size), 3) and that reported all 12 months of the year (i.e. reported in December but potentially not any other month).

When an agency reports 3-11 months, those months of data are multiplied by 12/numbers-of-months-reported so it just upweights the available data to account for the missing months, assuming that missing months are like the present months.

Finally, for agencies that reported all 12 months there is nothing missing so it just uses the data as it is.

Figure 10.6: The imputation procedure for missing data based on the number of months missing.

10.3.1 1-9 months missing

When there are 1-9 months reported the missing months are imputed by multiplying the reported months of data by 12/numbers-of-months-reported, essentially just scaling up the reported months. For example, if 6 months are reported then it multiplies each crime values by 12/6=2, doubling each reported crime value. This method makes the assumption that missing values are similar to present ones, at on average. Given that there are seasonal differences in crime - which tends to increase in the summer and decrease in the winter - how accurate this replacement is depends on how consistent crime is over the year and which months are missing. Miss the summer months and you will undercount crime. Miss the winter months and you will overcount crime. Miss random months and you will be wrong randomly (and maybe it’ll balance out but maybe it would not).

We will look at a number of examples and simulations about how accurate this method is. For each example we will use agencies that reported in 2018 so we have a real comparison when using their method of replacing “missing” months.

Starting with Table 10.2, we will see the change in the actual annual count of murders in Philadelphia when replacing data from each month. Each row shows what happens when you assume that month - and only that month - is missing and interpolate using the current 12/numbers-of-months-reported method. Column 1 shows the month that we are “replacing” while column 2 shows the actual number of murders in that month and the percent of annual murders in parentheses. Column 3 shows the actual annual murders which is 351 in 2018; column 4 shows the annual murder count when imputing the “missing” month” and column 5 shows the percent change between columns 3 and 4.

If each month had the same number of crimes we would expect each month to account for 8.33% of the year’s total. That is not what we are seeing in Philadelphia for murders as the percentages range from 5.13% in both January and April to 12.25% in December. This means that replacing these months will not give us an accurate count of crimes as crime is not distributed evenly across months. Indeed, as seen in column 5, on average, the annual sum of murders when imputing a single month is 1.85% off from the real value. When imputing the worst (as far as its effect on results) months you can report murder as either 4.27% lower than it is or 3.5% higher than it is.

| Month | Murders That Month | Actual Annual Murders | Imputed Annual Murders | Percent Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 46 (8.95%) | 514 | 511 | -0.58 |

| February | 38 (7.39%) | 514 | 519 | +0.97 |

| March | 40 (7.78%) | 514 | 517 | +0.58 |

| April | 34 (6.61%) | 514 | 524 | +1.95 |

| May | 56 (10.89%) | 514 | 500 | -2.72 |

| June | 52 (10.12%) | 514 | 504 | -1.95 |

| July | 55 (10.70%) | 514 | 501 | -2.53 |

| August | 46 (8.95%) | 514 | 511 | -0.58 |

| September | 40 (7.78%) | 514 | 517 | +0.58 |

| October | 42 (8.17%) | 514 | 515 | +0.19 |

| November | 25 (4.86%) | 514 | 533 | +3.70 |

| December | 40 (7.78%) | 514 | 517 | +0.58 |

Part of the reason for the percent difference for murders when replacing a month found above is that there was high variation in the number of murders per month with some months having more than double the number as other months. We will look at what happens when crimes are far more evenly distributed across months in Table 10.3. This table replicates Table 10.2 but uses thefts in Philadelphia in 2022 instead of murders. Here the monthly share of thefts ranged only from 6.85% to 9.16% so month-to-month variation is not very large. Now the percent change never increases above an absolute value of 1.62 and changes by an average of 0.77%. In cases like this, the imputation method is less of a problem.

| Month | Thefts That Month | Actual Annual Thefts | Imputed Annual Thefts | Percent Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 3,080 (6.41%) | 48,067 | 49,077 | +2.10 |

| February | 2,929 (6.09%) | 48,067 | 49,241 | +2.44 |

| March | 3,546 (7.38%) | 48,067 | 48,568 | +1.04 |

| April | 3,619 (7.53%) | 48,067 | 48,489 | +0.88 |

| May | 4,063 (8.45%) | 48,067 | 48,004 | -0.13 |

| June | 4,425 (9.21%) | 48,067 | 47,609 | -0.95 |

| July | 4,566 (9.50%) | 48,067 | 47,456 | -1.27 |

| August | 4,798 (9.98%) | 48,067 | 47,203 | -1.80 |

| September | 4,477 (9.31%) | 48,067 | 47,553 | -1.07 |

| October | 4,618 (9.61%) | 48,067 | 47,399 | -1.39 |

| November | 4,022 (8.37%) | 48,067 | 48,049 | -0.04 |

| December | 3,924 (8.16%) | 48,067 | 48,156 | +0.19 |

Given that the imputation method is largely dependent on consistency across months, what happens when crime is very rare? Table 10.4 shows what happens when replacing a single month for motor vehicle thefts in Danville, California, a small town which had 22 of these thefts in 2022. While possible to still have an even distribution of crimes over months, this is less likely when it comes to rare events. Here, having so few motor vehicle thefts means that small changes in monthly crimes can have an outsize effect. The average absolute value percent change now is 7.3% and this ranges from a -15.68% difference to a +9.1% difference from the real annual count. This means that having even a single month missing can vastly overcount or undercount the real values.

| Month | Vehicle Thefts That Month | Actual Annual Vehicle Thefts | Imputed Annual Vehicle Thefts | Percent Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 2 (7.41%) | 27 | 27 | +0.00 |

| February | 2 (7.41%) | 27 | 27 | +0.00 |

| March | 1 (3.70%) | 27 | 28 | +3.70 |

| April | 4 (14.81%) | 27 | 25 | -7.41 |

| May | 6 (22.22%) | 27 | 23 | -14.81 |

| June | 0 (0.00%) | 27 | 29 | +7.41 |

| July | 2 (7.41%) | 27 | 27 | +0.00 |

| August | 1 (3.70%) | 27 | 28 | +3.70 |

| September | 1 (3.70%) | 27 | 28 | +3.70 |

| October | 3 (11.11%) | 27 | 26 | -3.70 |

| November | 3 (11.11%) | 27 | 26 | -3.70 |

| December | 2 (7.41%) | 27 | 27 | +0.00 |

In the above three tables we looked at what happens if a single month is missing. Below we will look at the results of simulating when between 1 and 9 months are missing for an agency. Table 10.5 looks at murder in Philadelphia again but now randomizes removing between 1 and 9 months of the year and interpolating the annual murder count using the current method. For each number of months removed I run 10,000 simulations.74 Given that I am literally randomly choosing which months to say are missing, I am assuming that missing data is missing completely at random. This is a very bold assumption and one that is the best-case scenario since it means that missing data is not related to crimes, police funding/staffing, or anything else relevant. So you should read the below tables as the most optimistic (and thus likely wrong) outcomes.

For each number of months reported the table shows the actual annual murder (which never changes) and the imputed mean, median, modal, minimum, and maximum annual murder count. As a function of the randomization, the imputed mean is always nearly identical to the real value. The most important columns, I believe, are the minimum and maximum imputed value since these show the worst-case scenario - that is, what happens when the month(s) least like the average month is replaced. Since as researchers we should try to minimize the harm caused from our work if it is wrong, I think it is safest to assume that if data is missing it is missing in the worst possible way. While this is a conservative approach, doing so otherwise leads to the greatest risk of using incorrect data, and incorrect results - and criminology is a field important enough to necessitate this caution.

As might be expected, as the number of months missing increases the quality of the imputation decreases. The minimum is further and further below the actual value while the maximum is further and further above the actual value.

| # of Months Missing | Mean Imputed Value | Median Imputed Value | Minimum Imputed Value | Maximum Imputed Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Missing Data | 514.00 | 514.00 | 514.00 | 514.00 |

| 1 month | 514.08 | 517.09 | 499.64 | 533.45 |

| 2 | 514.12 | 513.60 | 483.60 | 546.00 |

| 3 | 513.81 | 513.33 | 468.00 | 556.00 |

| 4 | 514.15 | 513.00 | 457.50 | 565.50 |

| 5 | 513.95 | 514.29 | 444.00 | 577.71 |

| 6 | 514.05 | 514.00 | 434.00 | 594.00 |

| 7 | 514.45 | 513.60 | 424.80 | 612.00 |

| 8 | 513.85 | 516.00 | 411.00 | 627.00 |

| 9 | 513.02 | 512.00 | 388.00 | 652.00 |

This problem is even more pronounced when looking at agencies with fewer crimes and less evenly distributed crimes. Table 10.6 repeats the above table but now looks at motor vehicle thefts in Danville, California. By the time 5 months are missing, the minimum value is nearly half of the actual value while the maximum value is a little under 50% larger than the actual value. By 9 months missing, possible imputed values range from 0% of the actual value to over twice as large as the actual value.

| # of Months Missing | Mean Imputed Value | Median Imputed Value | Minimum Imputed Value | Maximum Imputed Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Missing Data | 27.00 | 27.00 | 27.00 | 27.00 |

| 1 month | 26.99 | 27.27 | 22.91 | 29.45 |

| 2 | 27.01 | 27.60 | 20.40 | 31.20 |

| 3 | 26.98 | 28.00 | 18.67 | 33.33 |

| 4 | 26.96 | 27.00 | 16.50 | 36.00 |

| 5 | 26.89 | 27.43 | 15.43 | 37.71 |

| 6 | 26.94 | 26.00 | 14.00 | 40.00 |

| 7 | 26.96 | 26.40 | 12.00 | 43.20 |

| 8 | 27.01 | 27.00 | 9.00 | 48.00 |

| 9 | 26.93 | 24.00 | 8.00 | 52.00 |

| # of Months Missing | Mean Imputed Value | Median Imputed Value | Minimum Imputed Value | Maximum Imputed Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Missing Data | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1 | 1.00 |

| 1 month | 1.00 | 1.09 | 0 | 1.09 |

| 2 | 1.00 | 1.20 | 0 | 1.20 |

| 3 | 1.01 | 1.33 | 0 | 1.33 |

| 4 | 1.01 | 1.50 | 0 | 1.50 |

| 5 | 1.01 | 1.71 | 0 | 1.71 |

| 6 | 1.01 | 2.00 | 0 | 2.00 |

| 7 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 2.40 |

| 8 | 1.01 | 0.00 | 0 | 3.00 |

| 9 | 1.01 | 0.00 | 0 | 4.00 |

10.3.2 10-12 months missing

In cases where there are more than 9 months of data missing, the current imputation method replaces the entire year of data for that agency with the average of the crime for agencies who reported 12 months of data, are in the same state and in the same population group as the given agency. Considering that when an agency reports data it tends to report every month of the year - and about a quarter of agencies still do not report any months of data - this is a far bigger issue than when agencies are missing 1-9 months of data. The imputation process is also far worse here.

Whereas with 1-9 months missing the results were at least based on the own agency’s data, and were actually not terribly wrong (depending on the specific agency and crime patterns) when only a small number of months were missing, the imputation for 10+ months missing is nonsensical. It assumes that these agencies are much like similarly sized agencies in the same state.

There are two major problems here. First, similarly sized agencies are based on the population group which is quite literally just a category indicating how big the agency is when grouped into rather arbitrary categories. These categories can range quite far - with agencies having millions more people than other agencies in the same category in some cases - so in most cases “similarly sized” agencies are not that similarly sized. The second issue is simply the assumption that population is all that important to crime rates. Population is certainly important to crime counts; New York City is going to have many more crimes than small towns purely due to its huge population, even though NYC has a low crime rate. But there is still huge variation in crimes among cities of the same or similar size as crime tends to concentrate in certain areas. So replacing an agency’s annual crime counts with that or other agencies (even the average of other agencies) will give you a very wrong count.

For this method of replacing missing data to be accurate agencies in the same population group in each state would need to have very similar crime counts. Otherwise it is assuming that missing agencies are just average (literally) in terms of crime. This again assumes that missing data is missing at random, which is unlikely to be true.

In each of the below examples we use data from 2022 Offenses Known and Clearances by Arrest and use only agencies whose final month reported was December. This makes it the actual agencies in each population group that would replace agencies that are missing 10 or more months of data in 2022. As agencies can - and do - report different numbers of months each year, these numbers would be a little different if using any year other than 2022.

For each population group we will look at the mean, median, and maximum number of murders plus aggravated assaults with a gun.75 This is essentially a measure of the most serious violent crimes as the difference between gun assaults and murders is, to some degree, a matter of luck (e.g. where the person is shot can make the difference between an assault and a murder).76 This is actually not available in NACJD’s county-level UCR data as they do not separate gun assaults from other aggravated assaults, though that data is available in the agency-level UCR data. If we see a wide range in the number of murders+gun-assaults in the below table, that’ll indicate that this method of imputing missing data is highly flawed.

Table 10.8 shows these values for all agencies in the United States who reported 12 months of data (based on the “December last month reported” definition) in 2022. The actual imputation process only looks at agencies in the same state, but this is still information at seeing broad trends - and we will look at two specific states below. Column 1 shows each of the population groups in the data while the remaining columns show the mean, median, minimum, and maximum number of murders+gun-assaults in 2022, respectively.77 For each population group there is a large range of values, as seen from the minimum and maximum values. There are also large differences in the mean and median values for larger (25,000+ population) agencies, particularly when compared to the top and bottom of the range of values. Using this imputation method will, in most cases (but soon we will see an instance where there is an exception) provide substantially different values than the real (but unknown) values.

| Population Group | Mean Murder | Median Murder | 90th Percentile Murder | Minimum Murder | Max Murder |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City Under 2,500 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| City 2,500-9,999 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| City 10,000-24,999 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 14 |

| City 25,000-49,999 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 31 |

| City 50,000-99,999 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 47 |

| City 100,000-249,999 | 9 | 6 | 23 | 0 | 122 |

| City 250,000+ | 86 | 40 | 237 | 2 | 499 |

| MSA Counties and MSA State Police | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 122 |

| Non-MSA Counties and Non-MSA State Police | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 46 |

| Population Group | Mean Murder | Median Murder | 90th Percentile Murder | Minimum Murder | Max Murder |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City Under 2,500 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| City 2,500-9,999 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| City 10,000-24,999 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 14 |

| City 25,000-49,999 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 31 |

| City 50,000-99,999 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 47 |

| City 100,000-249,999 | 9 | 6 | 23 | 0 | 122 |

| City 250,000+ | 86 | 40 | 237 | 2 | 499 |

| MSA Counties and MSA State Police | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 122 |

| Non-MSA Counties and Non-MSA State Police | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 46 |

Since the actual imputation process looks only at agencies in the same state, we will look at two example states - Texas and Maine - and see how trends differ from nationally. These states are chosen as Texas is a very large (both in population and in number of jurisdictions) state with some areas of high crime while Maine is a small, more rural state with very low crime. Table 10.10 shows results in Texas. Here, the findings are very similar to that of Table 10.8. While the numbers are different, and the maximum value is substantially smaller than using all agencies in the country, the basic findings of a wide range of values - especially at larger population groups - is the same.

| Population Group | Mean Murder | Median Murder | 90th Percentile Murder | Minimum Murder | Max Murder |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City Under 2,500 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| City 2,500-9,999 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| City 10,000-24,999 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| City 25,000-49,999 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 7 |

| City 50,000-99,999 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 9 |

| City 100,000-249,999 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 0 | 17 |

| City 250,000+ | 84 | 27 | 234 | 3 | 343 |

| MSA Counties and MSA State Police | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 121 |

| Non-MSA Counties and Non-MSA State Police | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9 |

Now we will look at data from Maine, as shown in Table 10.11. Here, results are much better: there is a narrow range in values meaning that the imputation would be very similar to the real values. This is driven mainly by Maine being a tiny state, with only one city larger than 50,000 people (Portland) and Maine being an extremely safe state so most places have zero murders+gun-assaults. In cases like this, where both crime and population size are consistent across the state (which is generally caused by everywhere having low crime), this imputation process can work well.

| Population Group | Mean Murder | Median Murder | 90th Percentile Murder | Minimum Murder | Max Murder |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City Under 2,500 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| City 2,500-9,999 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| City 10,000-24,999 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| City 25,000-49,999 | 7 | 1 | 16 | 0 | 20 |

| City 50,000-99,999 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| City 100,000-249,999 |

|

|

|

|

|

| City 250,000+ |

|

|

|

|

|

| MSA Counties and MSA State Police | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-MSA Counties and Non-MSA State Police | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 |

Even for county-level agencies such as Sheriff’s Offices, the data is only for crimes in that agency’s jurisdiction. So the county sheriff reports crimes that they responded to but not crimes within the county that other agencies, such as a city police force, responded to.↩︎

Because the county-level data imputes missing months, this data set is only available at the annual-level, not at the monthly level.↩︎

Full disclosure, I used to have my own version of this data available on openICPSR and followed NACJD’s method. My reasoning was that people were using it anyways and I wanted to make sure that they knew the problem of the data, so I included the issues with this data in the documentation when downloading it. However, I decided that the data was more flawed than I originally thought so I took down the data.↩︎

This chapter is not a critique of NACJD, merely of a single data set collection that they released using imputation methods from decades ago.↩︎

These problems are in addition to all the other quirks and issues with SRS data that have been discussed throughout this book.↩︎

For New York City specifically NACJD does distribute to all five counties, and does so by county population.↩︎

Even though these are unusual agencies, in real analyses using UCR data at the county-level you would like want to include them. Or justify why you are not including them.↩︎

Not the percentage point difference.↩︎

This is actually more than I need to run to get the same results..↩︎

Aggravated assaults with a gun include but are not limited to shootings. The gun does not need to be fired to be considered an aggregated assault.↩︎

Attempted murders are considered aggravated assaults in the UCR.↩︎

The agency-level UCR data actually has more population groups than this list, but NACJD has grouped some together. Given that some states may have few (or no) agencies in a population group, combining more groups together does alleviate the problem of having no comparison cities but at the tradeoff of making the comparison less similar to the given agency.↩︎