Chapter 14 Offender Segment

As might be expected, the Offender Segment provides information about who the offender is for each incident, though this is limited to only four demographic variables: age, sex, race, and ethnicity. In incidents with multiple offenders it provides information about each offender. While important factors such as criminal history, socioeconomic status, and motive are missing in the Offender Segment, other segments provide some supplementary details. For example, the Victim Segment reveals the relationship between the offender and victim, and the Offense Segment tells us whether a weapon was used by the offender. These pieces of information allow for a more complete picture, although they remain fragmented across segments.

In cases where there is no information about the offender there will be a single row where all of the offender variables will be “unknown.” In these cases having a single row for the offender is merely a placeholder and doesn’t necessarily mean that there was only one offender for that incident. However, there’s no indicator for when this is a placeholder and when there was actually one offender but whose demographic information is unknown.

The Offender Segment is the sparsest of the available segments, and provides only four new variables that are about the offender’s demographics.

14.1 Demographics

There are four demographics variables included in this data: the offenders’ age, sex, race, ethnicity. Please note that what we have here are not unique offenders as the same person can be involved in multiple incidents and therefore be counted multiple times. There’s no offender ID variable that is consistent across incidents so we cannot tell when an offender is involved with different incidents. So be cautious when trying to compare this with some base rate such as percent of people of each age, sex, race, or ethnicity in a population.

14.1.1 Age

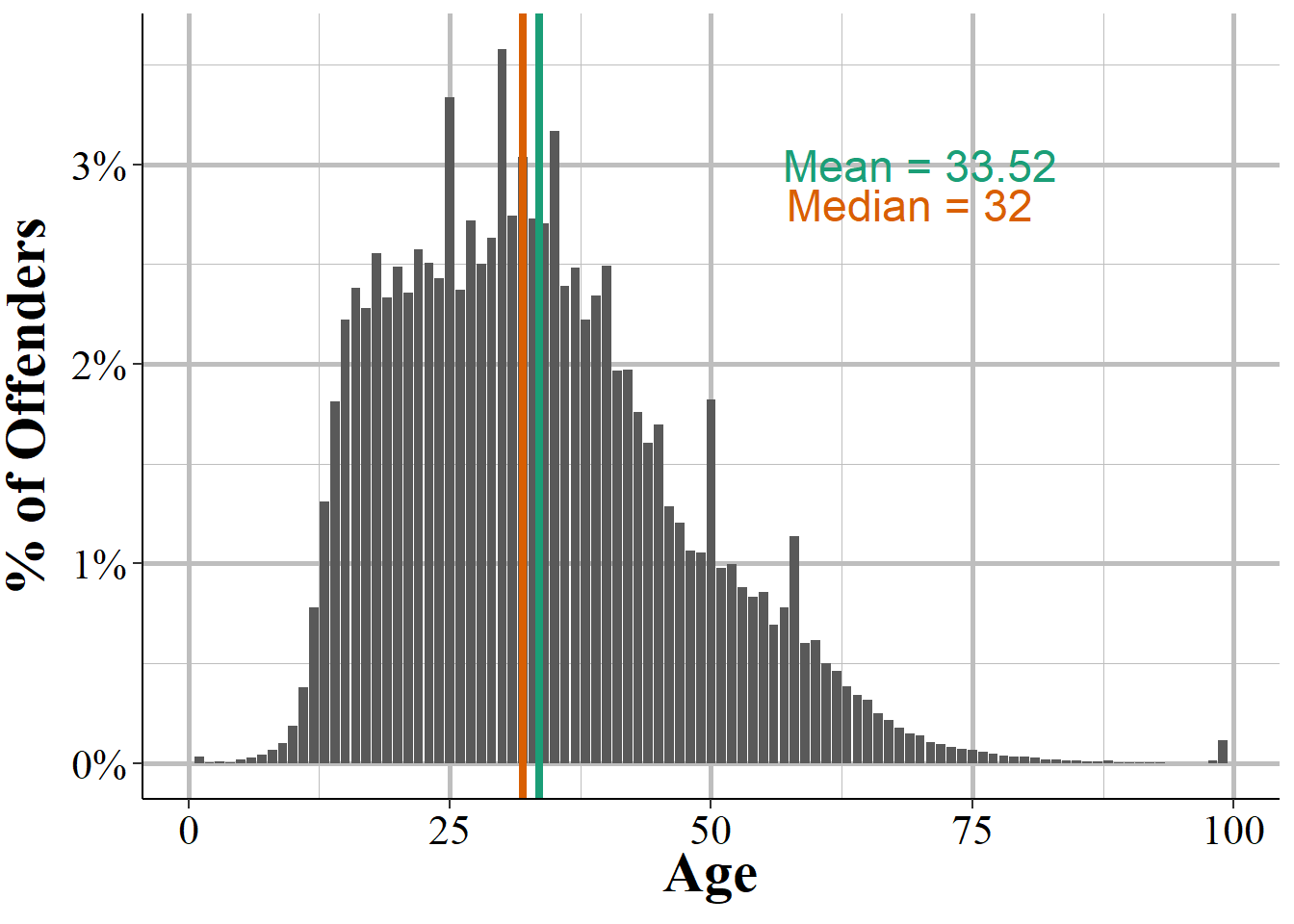

The age variable is the suspected age of the offender. This is presented to us as how many years old the offender is, however, agencies can input an age range if they do not know the exact age (e.g. age 20-29) and the FBI will convert that to an exact number by averaging it for us. So if the police say the offender is aged 20-29 (since they do not know for sure), we only see that the offender is 24 years old since the FBI averages the range and then rounds down to make an integer. This value is top-coded to 99 years old with everyone 99 years or older being set as “over 98 years old.” Figure 14.1 shows the distribution of offender ages for all known offenders in the 2022 NIBRS data. About 14% of offenders have an unknown age and are excluded from the figure.

This data supports the widely observed age-crime curve, which shows that criminal activity tends to peak in the late teenage years and gradually declines as individuals age. Interestingly, in the NIBRS data, the most common offender age is 25, indicating a slightly later peak. This shift could reflect changes in the types of offenses reported or evolving offender patterns over time. The age distribution can differ depending on what offenses the offender’s committed. To examine that you will need to merge this segment with the Offense Segment and then subset the offender data by the offense you are interested in.

Figure 14.1: The age of all offenders reported in the 2022 NIBRS data. Approximately 44 percent of offenders have an unknown age are not shown in the figure.

The spike you see at the very end of the data is due to the data maxing out possible individual ages at 98, so anyone older is grouped together. Surely very young children aren’t committing crimes, so is this a data error? Mostly yes. These entries likely reflect either data entry mistakes or situations where officers mistakenly input the offender’s age as “1” rather than selecting “unknown.” However, in rare cases, this could also include tragic incidents, such as accidental harm caused by a child handling a firearm, which are still recorded as criminal incidents despite no intent. However, the bulk of this, especially for age one, is likely just a data error or the police entering age as one instead of saying that the age is unknown (which they have the option of doing) or simply entering the data incorrectly by mistake.

Another indicator of guesses about age is that three of the five most common ages are 25, 30, and 20 years old. People tend to like multiples of five when making estimates, so these indicate that someone (the victim or the officer) probably did not know the exact age and so guessed the age or used an age range rather than the exact age.

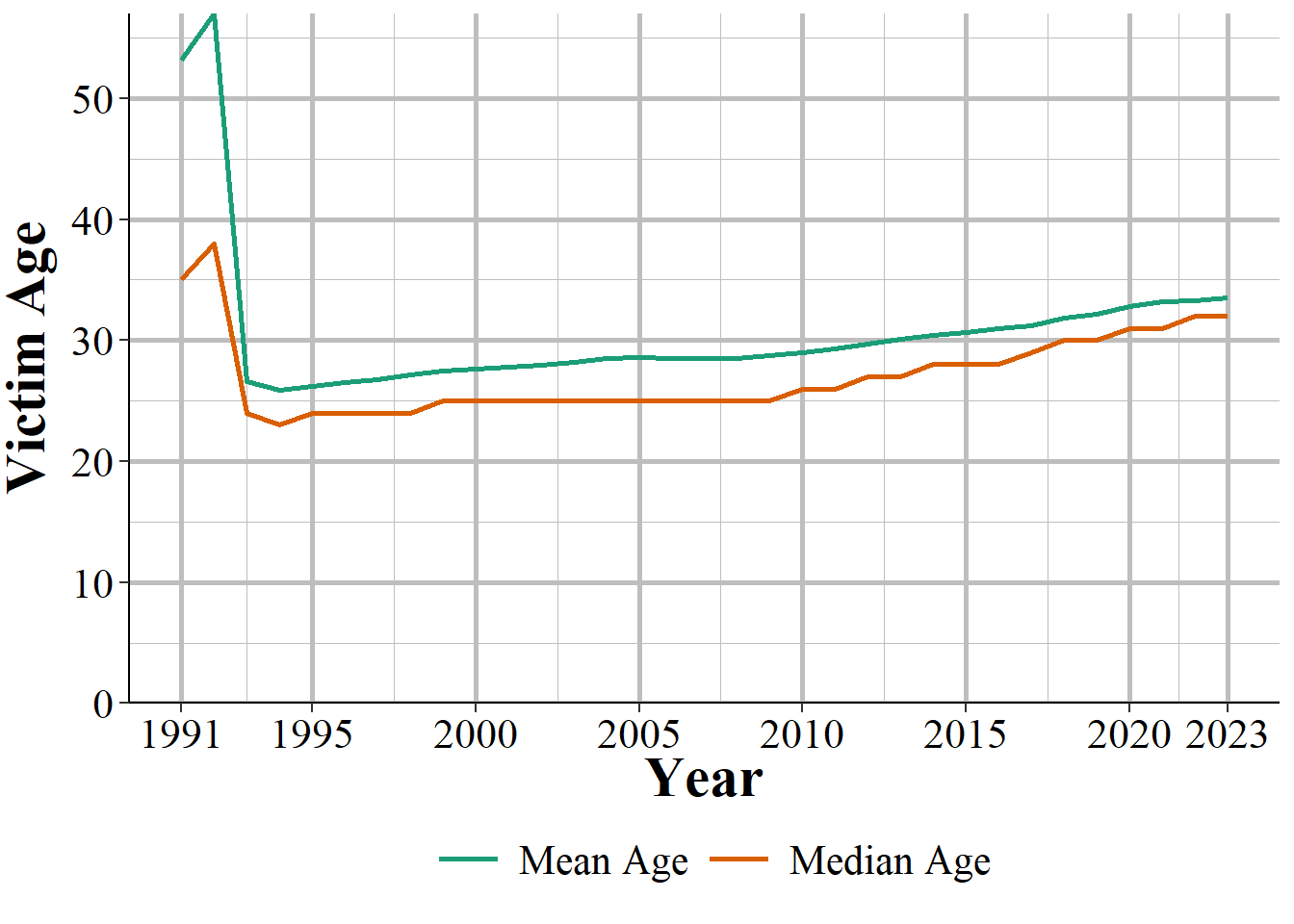

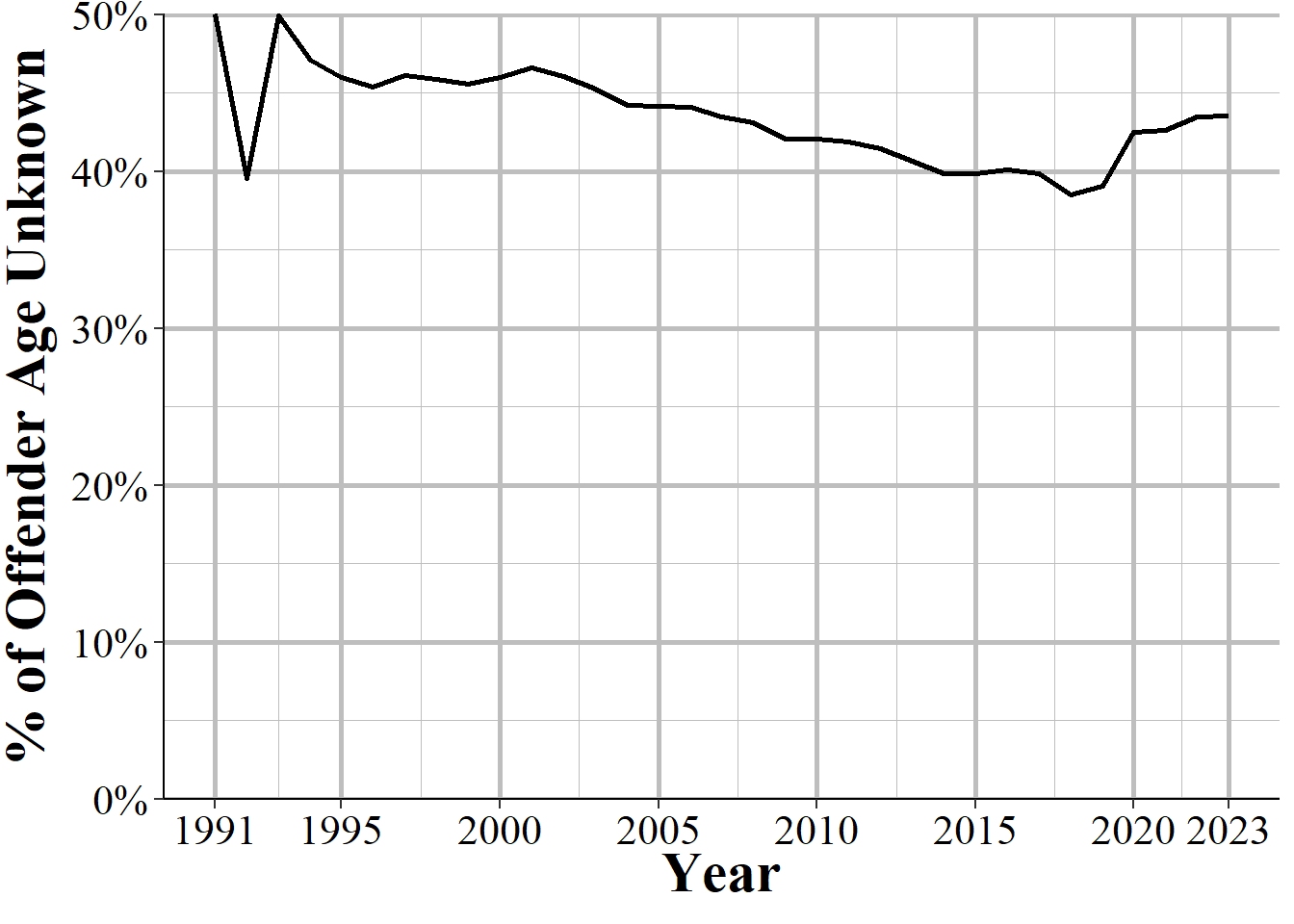

Since we have data since 1991 we can look at how age changed over time. In Figure 14.2 shows the annual mean and median age of offenders from 1991-2023. The first two years of data we see very old offenders91 with mean age over 50 and median age over 34 each year. That then drops considerably in 1993 to about age 25 and then starts a very slow and consistent increase over time until the average offender is in the early thirties by the latest years of data. Figure 14.3 shows the percent of offenders that have an unknown age which also has some odd and large movements in 1991-1992 then settles to a steady and slow declining trend in 1993 before reversing itself and increasing in the late 2010s.

So what do we make of these trends? The first thing to keep in mind is that we are doing something fairly dumb. Each year of data we have different agencies reporting meaning that differences over time may simply be due to different agencies providing data. Still, if we had to interpret it I would say that the values in 1991 and 1992 are due to data issues likely caused by growing pains from agencies just starting out using NIBRS. Luckily, since NIBRS data has information on every single offender - rather than being already aggregated like in SRS data - we can check this. Indeed, this appears to simply be a data issue where many agencies put the age of offenders as “over 98 years old” rather than identifying them as unknown. In 1991, for example, 36% of offenders who had a known age were reported to be older than 98 years. When we look at the average age in 1991 when excluding people 99+ years old we get 28 years old, perfectly within expectation when looking at averages after 1992.

Figure 14.2: The mean and median age of offenders, 1991-2023.

Figure 14.3: The percent of offender’s age that is unknown, 1991-2023.

14.1.2 Sex

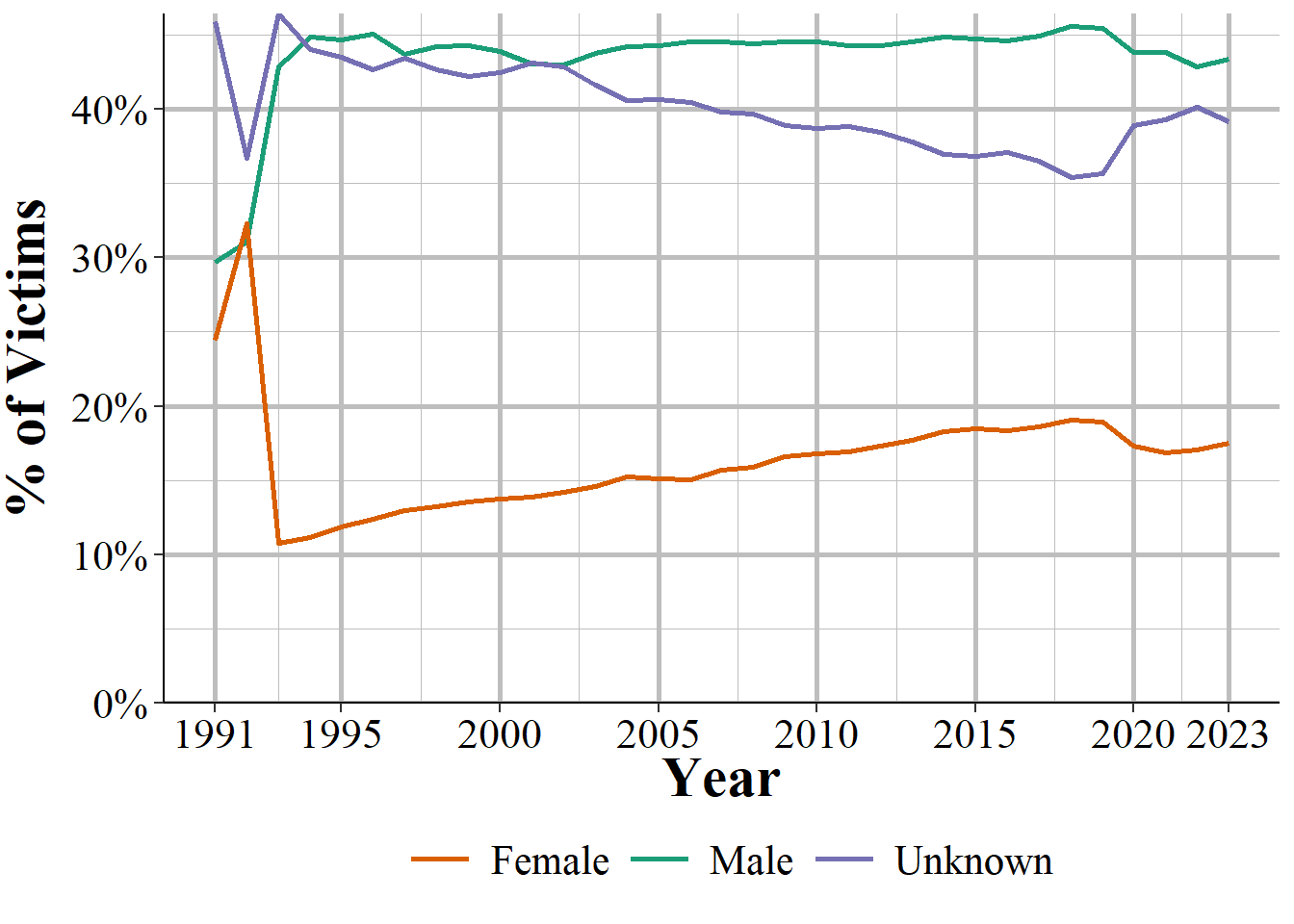

The second offender demographic variable available is the offender’s sex with male and female being the only available sexes. There is no option for transgender or anything else. Other than arrestees, where police could (though we do not know if they do) use their identification (e.g. driver’s license) to determine their sex, this is likely the perceived sex of the offender based on what evidence the officer can collect (e.g. witness statement, video recordings, driver’s licenses of the offender if they are caught, etc.). Figure 14.4 shows the distribution of offenders by sex for each year of data. The most common sex is male, which is consistent with the literature on who commits crime. About 45% of all offenders were male. Female offenders make up fewer than 20% of offenders though the general trend is that the share of offenders is increasing. Over a third of offenders have an unknown sex with the share being unknown decreasing over time until increasing again in the last several years. Considering that when nothing is known about offenders (including even how many offenders there are) this data includes a single row with “unknown” for all demographic variables, this is actually an undercount of offenders who have unknown sex. Again we see odd results in 1991 and 1992, likely an issue with data entry at the birth of NIBRS.

Figure 14.4: The share of offenders by sex, 1991-2023.

14.1.3 Race

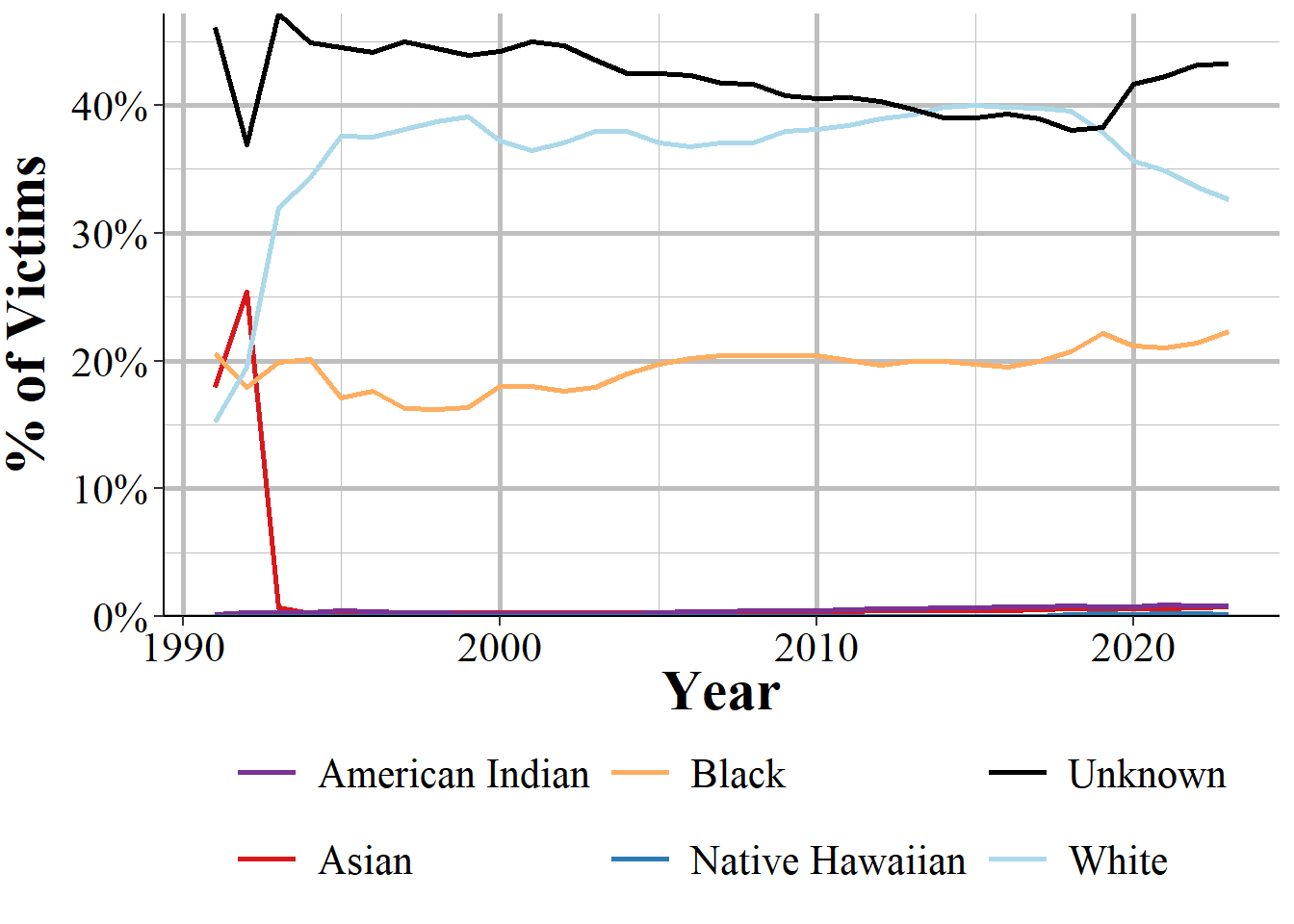

The next variable is the race of the offender, categorized as White, Black, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander. It is important to note that this is often the officer’s perception of race, which can introduce bias or inaccuracies, particularly in cases where there was no arrest or detailed witness account.

Figure ?? shows the breakdown in offender races for every offender in our data. The most common offender race in nearly every year is Unknown, with about 40% of offenders not having a known race. This is actually an undercount as in cases where the agency does not know anything about the offenders they will put down a single offender with “unknown” for every demographics variable. So there could potentially be multiple offenders represented when there is a row with an unknown offender race. This is also dependent on the type of crimes committed and when they are committed. For example, a daytime robbery would likely have a known offender race as the victim can clearly see (complexities about identifying people’s race aside) the race of the robber. A daytime burglary where no one is home would likely have an unknown offender race and there would be no witnesses. Likewise, a robbery at night could have an unknown offender race because the darkness makes it harder to identify people.

The next most common offender race is White at a bit under 40% in most years, followed by Black at around 20%. The remaining races make up very few offender and are hard to see on the figure. We still see the weird values in 1991 and 1992, this time showing a massive spike in the number of Asian offenders which disappear to less than 1% in 1993. This corresponds to spike in White offenders in 1993, suggesting that some White offenders in 1991-1992 were incorrectly identified as Asian.

Figure 14.5: The share of offenders by race, 1991-2023.

14.1.4 Ethnicity

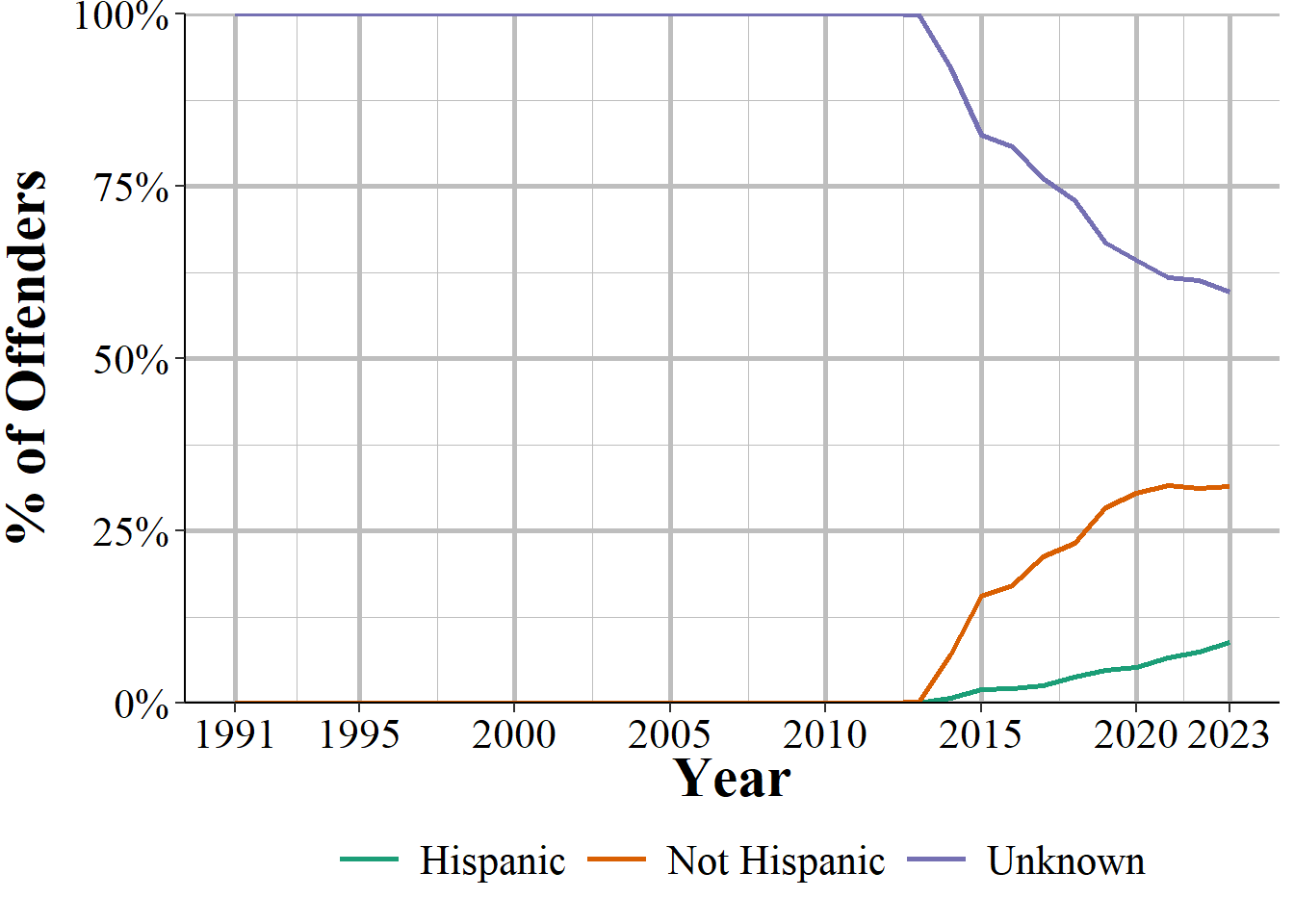

Ethnicity data, collected sporadically starting in 2013, is rarely recorded, with the most common entry being “unknown.” As we can see in Figure 14.6 this variable is very rarely used and for most of the life of NIBRS it was not collected. Even when it was collected - which started in 2013, ended after 2016, and then returned in 2021 - the most common value is that the offender’s ethnicity was unknown.

Figure 14.6: The share of offenders by ethnicity, 1991-2023.

While the Offender Segment is limited to basic demographics, it remains a valuable resource for identifying broad patterns in offender behavior. By tracking trends over time, researchers can examine shifts in age, sex, and race among offenders, which may inform policy decisions on crime prevention and law enforcement strategies. However, gaps in the data - such as unknown offender details, new agencies reporting data each year, and the absence of critical variables like criminal history - highlight the need for cautious interpretation and cross-referencing with other data sources.

At least in terms of expected age of offenders.↩︎